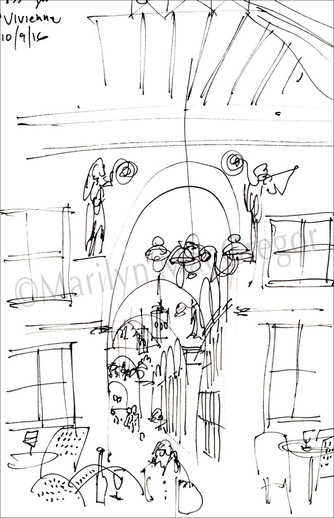

Galerie Vivienne by Marilyn MacGregor

Galerie Vivienne by Marilyn MacGregor I’ve been in France for a couple of weeks; some business having to do with my ArtSmartTravel tours, a good deal of drawing in order to add more Paris and France to my MacGregor-Art International Series of fine art prints, and also just to be here in a place I love and know well. I never expect much from the weather but this time it has been just as beautiful as the city of Paris and the countryside of France. I’ve spent some time in museums, of course – a small Rembrandt show at the Jacquemart-Andre Museum, a retrospective of Fantin-Latour at the Luxembourg, a few hours in Lyon’s Musée des Beaux Arts and, yesterday, the Louvre. There is always something new to learn, but especially at the Louvre it was kind of an Old Home Week, a chance to revisit works I may or may not love outright, but taught for long enough to feel on intimate terms with them. The most enjoyable part of the Louvre, as in most big museums, is finding the quiet corners with interesting works that are able to speak clearly without having to shout over the crowds. I had that pleasure when I came across a gathering of paintings by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, who lived and worked in the 18th century, a time when most artists were under the heavy thumb of academic strictures. Unlike most of his contemporaries with their grandiose portraits and history paintings, Chardin created small quiet genre scenes and still lifes. Yet, despite swimming against the Baroque and Rococo tides, he prospered nicely; Diderot, eminent spokesperson for the Enlightenment, was especially fond of his still lifes.

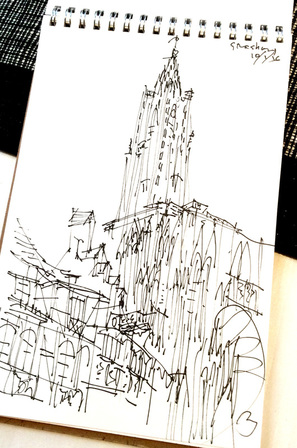

Strasbourg Cathedral by Marilyn MacGregor

Strasbourg Cathedral by Marilyn MacGregor Chardin is a great role model for artists – for me he reminds me that my way of working is my way of working. I treasure as subjects things often overlooked or thought unimportant in the grand scheme but which reveal everything about human existence on earth. I have a sophisticated understanding of art periods and the context of art in world history, but I love above all the simple spontaneous act of drawing, both in my own work and in that of others. As I get older, with my drawing, I’m less inclined to worry about every small detail – I like hinting rather than spelling out, and work to capture the energy of life as it speeds by. If it means that my drawings look tossed off, well some of them are – I work very quickly, with the confidence of long practice – and I also cannot help that a bit of whimsy invariably makes its way into my stew of lines on a page. But what better definition of life? Life goes by too fast, and to make it through we do best to keep a sense of humor.

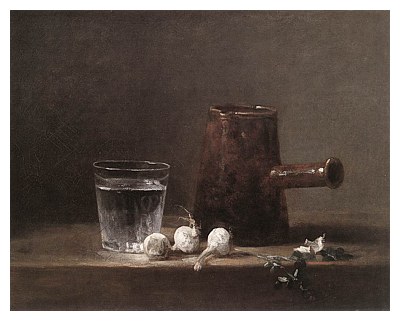

Water Glass and Jug by Chardin 1760

Water Glass and Jug by Chardin 1760 At the risk of hubris here are a few words about a typical Chardin and then one of my drawings.

Try to look at this little painting with 18th c eyes – what could possibly make anyone care about it when there are so many grand canvases? This still life is so mundane and dull – no silver knife, no flowers, no crystal glass of wine. But it is exquisitely painted with a mastery of form and texture, and there is much more to see than meets the initial glance. Water, for example – the simplest of substances presented in a simple glass – but nothing simple about our need for it: life doesn’t exist without it. A copper jug, banged up a bit by use: I think that’s us, battered and dropped by life now and then, but still of use as we age. A few turnips? Sustenance, if not luxury. And air? As invisible in reality as it is in this composition, but crucial in both instances.

Try to look at this little painting with 18th c eyes – what could possibly make anyone care about it when there are so many grand canvases? This still life is so mundane and dull – no silver knife, no flowers, no crystal glass of wine. But it is exquisitely painted with a mastery of form and texture, and there is much more to see than meets the initial glance. Water, for example – the simplest of substances presented in a simple glass – but nothing simple about our need for it: life doesn’t exist without it. A copper jug, banged up a bit by use: I think that’s us, battered and dropped by life now and then, but still of use as we age. A few turnips? Sustenance, if not luxury. And air? As invisible in reality as it is in this composition, but crucial in both instances.

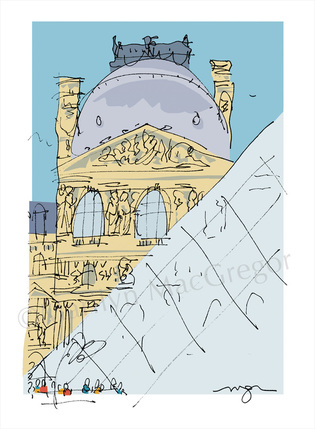

The Louvre by Marilyn MacGregor

The Louvre by Marilyn MacGregor Again, I’m no Chardin, but here is one of my Paris scenes, created from a sketchbook drawing on an earlier trip. Chardin, who was born in Paris and never in his life traveled, would recognize the Louvre – sort of. In his day the Louvre was run-down and practically abandoned because the Bourbon Kings didn’t care to live in Paris. The Louvre we know today – even without the 1970’s pyramid – is a clean, majestic dream destination for art-lovers. So my drawing, while very different in subject from Chardin’s Water Jug and Glass, contains its own layers. The grandiose history of the Louvre is represented, or at least implied, by my sketch of the façade in its ornate sculpted Renaissance splendor. The pyramid by I.M. Pei serves a practical purpose as the principal entry to the Louvre, but as all photographers know, it is most exciting for the reflections of the historical Louvre that surrounds it on three sides. The Louvre Pyramid adds a major contemporary note while also emphasizing the grandeur of the original structures. And, in my drawing as in Chardin, there ‘we’ are, resting our weary tourist feet, calming our squalling children, snapping selfies, conscious or unconscious of the looming presence of kings, great art, great architects, historical events and deeds filling the space all around us.

Watch my website www.macgregor-art.com for new International Scenes as well as my Philadelphia series and my happy tribe of Dogs and Cats.

Questions about ArtSmartTravel? email [email protected]

Questions about MacGregor-Art? email [email protected]

Watch my website www.macgregor-art.com for new International Scenes as well as my Philadelphia series and my happy tribe of Dogs and Cats.

Questions about ArtSmartTravel? email [email protected]

Questions about MacGregor-Art? email [email protected]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed